Why NATO’s 5% Defense Target Is a Necessary Sacrifice for Europe

Source: Wikimedia Commons / Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III speaks with colleagues at NATO headquarters, Brussels, Belgium, June 16, 2023

Early last month, staff editor Sreejani Sinha published a piece in The Compass with a bold argument: NATO’s decision in June 2025 to increase national defense spending from a 2% minimum to 5% represented a reckless shift to a “wartime mindset,” which could deter threats, but at the cost of militarizing Europe and fueling a dangerous rift between Western citizens and their public institutions. In other words, by moving the needle to 5%, European NATO partners have prioritized a robust military posture over diplomacy, humanitarian action, and democratic stability.

Sinha’s diagnosis of the diverse challenges facing the European side of the ‘Euro-Atlantic Bloc’ is broadly correct. From Brussels to Tallinn, governments – and the European Commission – must carefully navigate a whirlwind set of crises: rising costs of living, unemployment, aging populations, disruptive innovations in Generative and Agentic AI, extraregional humanitarian crises like Sudan and Gaza, ‘black swan’ epidemic disease events, and fragile post-COVID supply chains. However, Sinha’s policy analysis is flawed in logic, inaccurately showcasing these challenges as (a.) significantly tied to fluctuations in defense spending and (b.) occurring in what amounts to a geopolitical vacuum.

A Continent Struggling for Prosperity

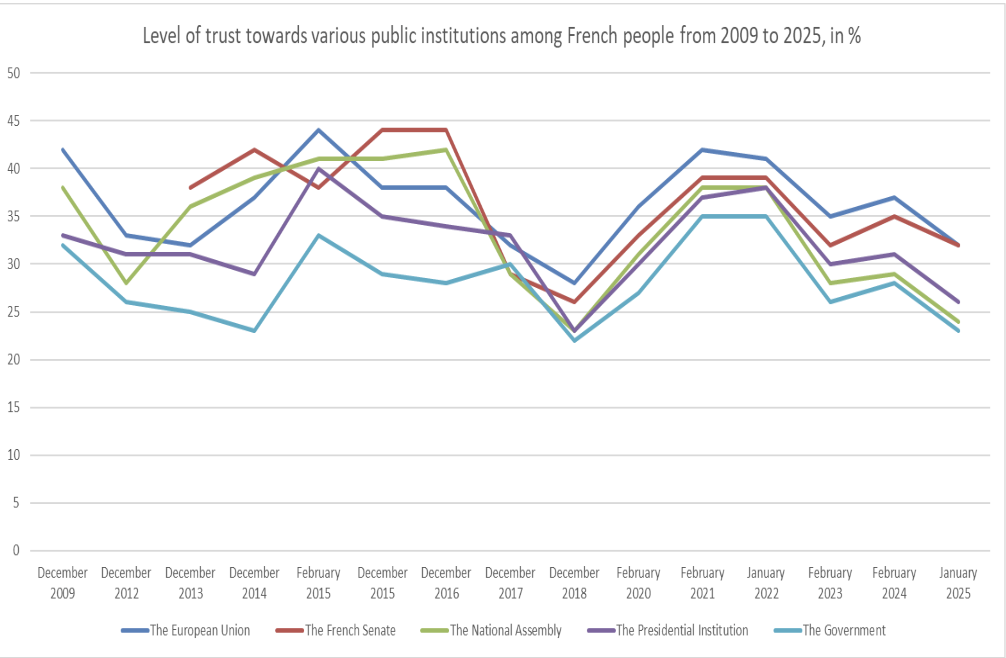

Let us consider the first critique through a case study of a major European power: France, which serves not only as the only Western-aligned continental nuclear power but also as one of the most consistent state advocates for a Europe that is more coordinated and autonomous in its defense posture. As demonstrated by Figure A, considering the period between the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2025, French society’s confidence in both national institutions and the European Union has been consistently low; no institution has ever gone above 50%, and trust is currently at a low point unseen since 2018. This widespread disillusionment in the state and EU to maintain order, protect society, and provide economic growth is also reflected in an approximately decade-long history of national social unrest, from the 2018-2020 ‘Gilets Jaunes’ to the recent ‘Bloquons Tout’ movement. Notably, the biggest episodes of upheaval have been almost completely disconnected from the ‘old guard’ of institutions built to organize pressure against the national government, including labor unions and traditional parties. Such phenomena reflect a broader anti-establishment trend among the French nation.

Figure A. Chart showcasing French level of trust, in %, toward the European Union, the French Senate, the National Assembly, the Presidency, and the Government, December 2009 to January 2025. Data from OpinionWay & Sciences Po (CEVIPOF), published in February 2025. Visualization created by author.

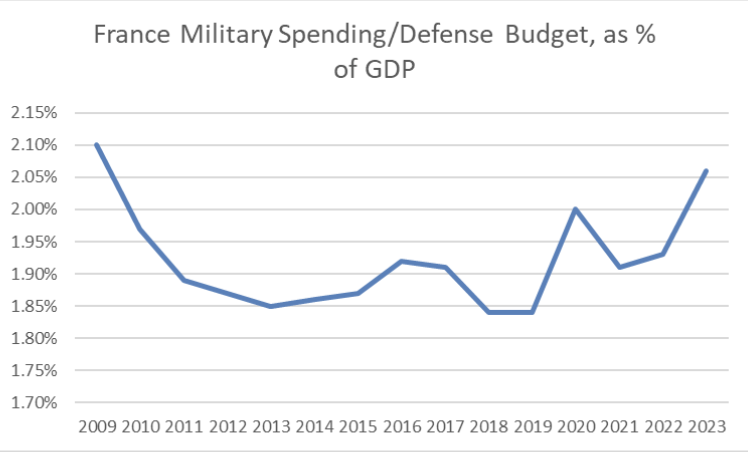

Looking at Figure B – French national defense spending – it becomes clear that the money Paris invests in its military posture has little association with how much trust the French people have in their institutions. Instead, as Prem Bahadur Manjhi of the University of Calcutta demonstrates through a chronological overview, public opposition and protest have centered around the fact that successive presidencies have dismantled old welfare systems created to allow the gears of democracy to turn throughout the 20th century. This includes to a certain extent the socialist Hollande interregnum, which also adopted an unpopular and inefficient politics of austerity. Similar trends of dissatisfaction and disillusionment, with relative variations based on electoral results, extent of adoption of neoliberalism in the late 20th century, and geopolitical alignment in the Cold War, exist in nearly every country of the NATO alliance, European or North American.

Figure B. Chart showcasing French national defense spending, in % of GDP, going toward the military and national defense, 2009 to 2023. Visualization created by author.

Of course, this year’s NATO consensus to increase defense spending to 5% – if national parliaments manage to agree on respective budgets and abide by the June commitment – will likely put strain on France and other European states’ ability to sustainably fund what is left of the welfare state and provide for economic growth that is not directly tied to the expansion of national defense industrial bases (DIBs). However, the central problem here is not that a swing to 5% will fundamentally break the state’s ability to meet the needs of tomorrow and potentially break Western democracy as we know it. Rather, Western states have since at least 2008 failed to manage the financial resources they already have to make the social welfare systems of yesterday work for the needs of today, thus putting at risk the stability of democratic life long-term. Like austerity, limiting defense spending increases now will do nothing to fix the issue; radical collective action at local, national, and EU levels must instead be taken to create new systems fit for the fractured and transforming societies of the 21st century.

What that collective action entails as actual policy is, admittedly, difficult to predict accurately due to Europe’s socio-political diversity and our current temporal positionality, where our attention to escalating crises globally impedes our ability to see far into the future. However, it is safe to say that nearly all steps will entail either trying to expand capacity beyond the present ‘constrained state’ paradigm, or to use existing capacity to cope with emerging constraining trends. In the former sphere, it may mean a large-scale opening up of national immigration systems to bring in human capital and prevent the depopulation of small towns, with increases in budgetary outlay and personnel hiring not only to handle heightened caseloads but also to integrate migrants comprehensively into their new home’s socio-cultural fabric. In some cases, radical action may mean the creation of a mandatory, one-year national or pan-European service. In this instance, national service could even be a primarily non-military project to build public works, compensate and train young adults in essential skills, and respond to the climate emergency, from wildfires in Sweden to rising sea levels in the Aegean.

In the latter sphere, it may mean curtailing the scale of technology integration in primary and secondary schooling, reflecting emerging research on how AI could be harming the future generations’ brain development and mental health. It may even mean European governments taking a much harsher tone toward the AI sector, with special clearance for researchers wanting access to advanced algorithms, strict regulation of ordinary Large Language Models, and the rapid expansion of European security and intelligence apparatuses to protect society from AI-facilitated disinformation, fraud, and terrorism.

The above proposals are only a fraction of what could ultimately achieved to bring European societies to new heights in the 21st century, yet few to none carry the political will to implement them today. Instead, the unrelenting pace of international conflict – not to mention anxieties over national unity and democratic backsliding – dominate political conversations from Warsaw to Lisbon.

A Continent That Must Mobilize

However, the ability for any such radical action to be taken in the long-term is fundamentally predicated on the central imperative for all states under a structural realist framework: survival. Sinha – like many on the ‘restrained’ side of the Washington foreign policy establishment – acknowledges that Europe is operating in an uncertain strategic environment that includes the war between Russia and Ukraine, the rise of China, and the spread of misinformation online. While that is technically valid, these threats are not equal in stature and immediacy, nor is these threats’ stature across European capitals equivalent to their significance for decision makers in the US. Put simply, while Washington has ‘room to breathe,’ Moscow’s aggression represents for Europe the critical challenge for the continent’s modern freedom and stability.

It bears reminding that even since the early years of the post-Cold War order, Moscow has acted aggressively against states it considers its rightful ‘Near Abroad’ in the European region. In 1992, the Russian military under Boris Yeltsin supported Russian separatists in Moldova, partitioning the country and impeding its European integration to this very day. In 2008, Moscow invaded Georgia, extending de facto control over South Ossetia and Abkhazia and blockading President Mikeil Saakashvili’s Western pivot. In 2004, the Kremlin tried to maintain influence over Ukraine through political technologists during Kyiv’s presidential election, though its actions were ultimately nullified through the Orange Revolution that brought the more Western liberal Viktor Yushchenko to the Bankova. Russia violated Ukrainian sovereignty once again in 2014, annexing the Crimean Peninsula and inflaming a hot war in Donetsk and Luhansk by Moscow-backed (and Russian military-staffed) separatists after Kyiv underwent a pro-EU democratic revolution. And that is not to understate the nearly 4-year war that Russia has thus far waged against Ukrainian independence outright, seeking to wrest vast territories from Kyiv and put its forces on the very doorstep of the NATO eastern frontier.

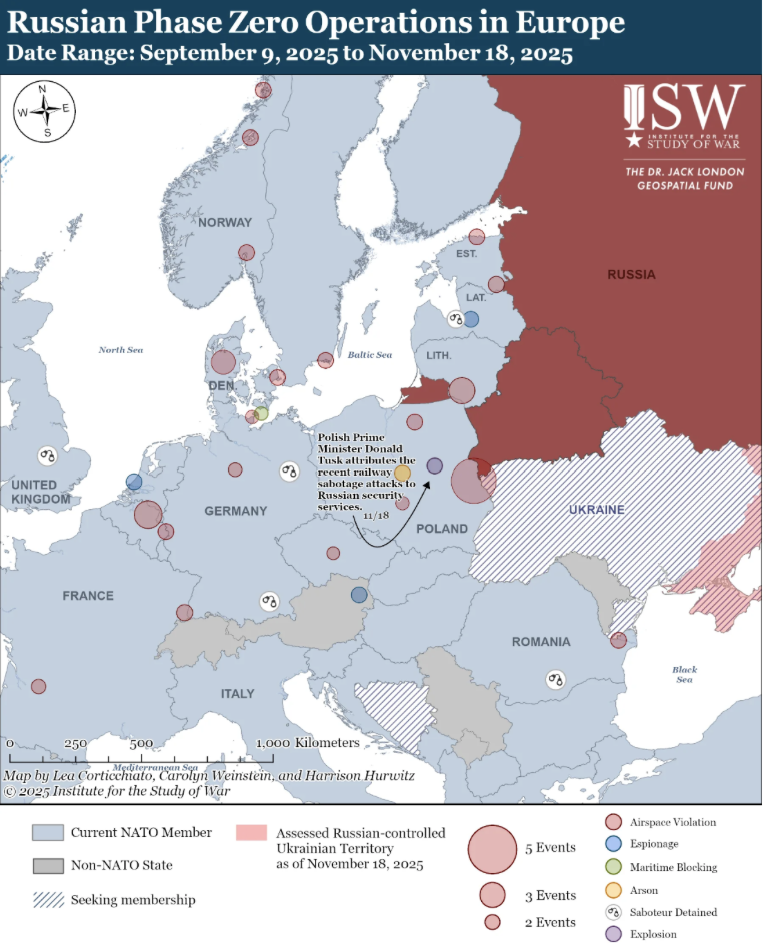

And Russia’s offensive ambitions clearly go further than non-NATO Europe. Since 2022, Russian officials have made thinly veiled threats of nuclear strikes on London, Paris, Brussels, and other capitals, while state media and online disinformation operations have tried to deny Russian war crimes and portray EU and NATO actions in support of Ukraine as warmongering. While both of these patterns of behavior constitute part of Moscow’s “hybrid war” (a popular term Sinha uses just once in passing), this framework is often far too vague to contextualize what damage Moscow has done inside the NATO bloc. Between 2011-22, for example, Russian military intelligence agents attempted to assassinate double agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, successfully exploded Czech munition depots, detonated a Bulgarian artillery shipment, and built extensive spy networks from the European Parliament to the International Criminal Court. In the last months of 2025, such hostility skyrocketed: despite not counting many Russian ‘shadow fleet’ and/or Electronic Warfare actions (e.g., GPS spoofing), the Institute for the Study of War now assesses Moscow to be well into “Phase Zero” operations, reflecting Moscow's setting the conditions for a potential future Russia-NATO War.

If Kyiv is left to complete defeat due to European complacency or US abandonment (or perhaps direct collusion with the Kremlin), then the risk that Russia will initiate a long-feared conventional attack – such as in Estonia, where NATO has prepared to lose land for at least half a year in an invasion scenario – will become substantially higher. In turn, increasing defense spending by all NATO nations will become more necessary than ever before, lest Moscow once again gamble in a moment of Western weakness. True, that spending will have to be utilized wisely on a wide range of conventional forces autonomous from the increasingly unreliable and slow American military-industrial complex, not just on over-hyped and over-engineered projects like the European Drone Wall. However, the overcoming of the long-bemoaned commitment hurdle remains worth celebrating as a sign of Europe waking up from its long slumber.

If Western support for Kyiv continues while a ceasefire is reached, however, then increased defense spending will also remain necessary: Russia, even if it only gets a small victory in Ukraine, remains a dangerous actor, one that remains guided by a revanchist ideology and holding a battle-hardened force. A partitioned-yet-sovereign Ukraine will need all the European industrial base it can get to make its independent defense viable and security guarantees credible. Further, a Russian offensive pivot to yet-vulnerable areas like the Baltics – whether to escalate Moscow’s battle against the West, score cheap territorial gains, or prevent the veterans of the so-called ‘special military operation’ from taking national leadership – clearly remains an all too attractive gamble to Putin and the security organs. A 5% minimum, if widely honored, will thus help escalate European DIBs to meet both bloc deterrence needs and the needs of a wartime and post-ceasefire Ukraine.

Evidently, in a time of socio-economic and geopolitical crisis, gearing up defense spending is a costly yet necessary PR decision, especially if national budgets are utilized wisely to escalate Europe’s conventional capabilities and achieve strategic autonomy. NATO’s June 2025 decision is thus ultimately long overdue to meet the existential challenge of an eastern aggressor that only listens to strength. If the bloc succeeds in honoring its tall commitment, it will also give a free Europe of tomorrow the opportunity to develop 21st century solutions to economic welfare and democratic stability problems plaguing it today.